The story of success of early-stage technological invention is not pretty. Studies from the US, Europe, Israel and Australia all say technological inventions are mostly unsuccessful.

One local study puts it like this, success appears to be the outlier and failure the norm. Worse it’s very hard to pinpoint specific factors of failure. A local study says it’s just a very wide spectrum of failure rather than anything very specific.

In this same study of a large local institution’s spinouts, all can be deemed to have failed. A major longitudinal study out of the University of Edinburgh’s Innovation Studies Group found that all the technology inventions they studied, failed to make their mark in the market.

The reason, the Edinburgh school says, is the designers’ assumptions that the users must conform to the technology’s functionality or the users were just ignored. The Israeli study on early-stage technology failure is just as concerning, finding that technology users appeared to be ignored.

The studies indicate many other failure factors, from board to financial, staffing, skill shortages and user problems. This list goes on. It appears everyone has their pet reasons and for good reason their experience points them in a direction where they can make sense of this messy concept of failure.

I have had close to a dozen commercialisations that have had many of these problems but chiefly these arise early in the piece with user technology relationship issues that are never quite resolved, leading to the final failure.

The Australian study bears this out calling it a dialectical tension between technology and the user. This happens when step one of the commercialisation process is not thoroughly and fully described and understood.

Einstein’s famous saying “we either succeed or learn”, may not actually be true with technological inventions, because we don’t know what it is we need to learn, and the research indicates this.

There may be a way out of this mess if we get step one right. And that is have a full and thorough understanding of the circular relationship between the technological invention and the technology user.

Unbelievably, European and Australian studies recognise that this circular relationship between the technological invention and the user is very poorly understood. Many marketers say this is just because designers and inventors don’t apply Marketing 101 – the studies disagree and so do I.

Marketing has no way to classify a technological invention and there are over 20 ways marketing classifies the invention product space, and most of these classifications make no logical sense. Plus, marketing has no way to classify user functionality. Often, the needs of the user group are not clear by any stretch of the imagination.

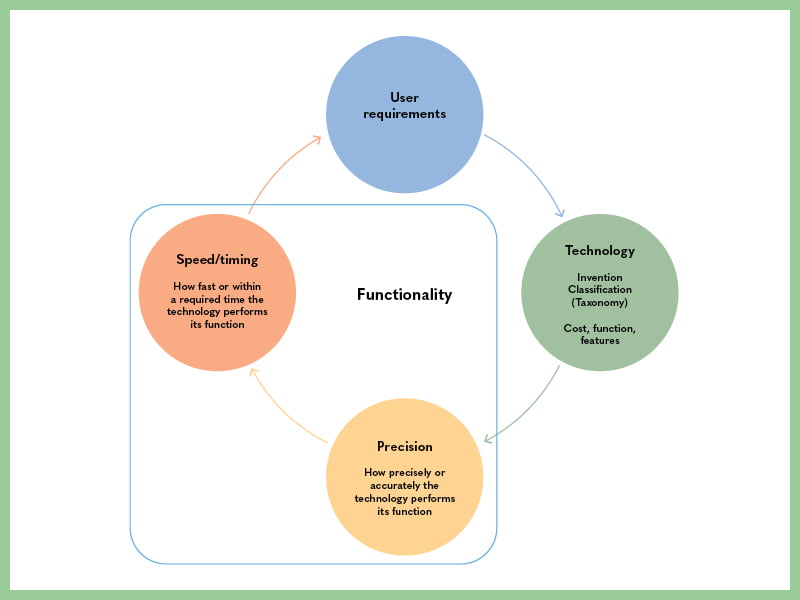

Step one out of the failure cycle, is having a clear and unambiguous way to thoroughly describe a technological invention (a ‘taxonomy’) and its technological users in a circular manner.

Step One is getting this right, it assists potential users, policy makers, investors, designers, patent lawyers and other eco stakeholders, to have a clear, logical understanding of the technological invention.

For simplicity we could call Step One the ‘3 by 3 by 3 Process’; the three technological invention types (taxonomy); the three categories we use to describe the technological invention, and; the three ways we measure the functionality (how well it does it) of the technology in relationship to the user. See diagram below.

The 3X3X3 Process

The technological invention types (taxonomy) tell us everything we need to know about the technological inventions’ design, composition and organisation – its full features. Let’s call them, Type 1, 2, 3.

These describe and classify every technological invention and have been tested against 50 inventions. These types then describe thoroughly the nature of the technological invention without any ambiguity.

The three categories of description, features-functions-functionality, give us the full overview of the technological invention.

The three measures (criteria) of functionality, cost, precision and timing tell us everything we need to know how well the technological invention performs in relation to the user. That is how well the technological invention carries out the tasks it was designed to do. Is it cheaper, better and faster?

Many of the early failures of technology in the studies have totally failed to understand this crucial part of the commercialisation process. This is where one can say the rubber meets the road with the technology and it’s somewhat easy to test these three criteria.

Why is it important to know all of this about technological inventions?

If a technological invention cannot be thoroughly and completely described with its features (taxonomy/classification), functions (what it does) and functionality (how well it does it), how can we expect a user group to understand its utility, efficacy and usefulness? How then is it possible for the user group to be able to interact harmoniously with the technology and validate it?

A thorough and complete description of a technological invention may reduce the high failure rate of early-stage technology start-ups and may increase the chances of user adoption and interaction.

How can we expect a user group to adopt and interact with a technology when the functionality is not fully understood by designers and inventors themselves? Ask any patent lawyer about how well inventors describe their inventions effectively for patenting. Generally, the answer is terrible.

The high-tech start-up sector in Australia is central to the economic growth plans of the federal government. Understanding robust early pathways to success are desirable for commercial viability – this includes the understanding of pitfalls and problems that may lie ahead of early-stage, high-tech start-ups with patentable technology inventions.

This is critical know-how for would-be entrepreneurs, founders, designers, academics, public officials, patent lawyers, policymakers and other entrepreneurial ecosystem stakeholder.

The ‘3X3X3 Process’ might stem the current high failure rate of spinouts and startups in Australia. Catching the issues early in the piece may reduce failure and the costs of failure both from a financial and social point of view.

The methods described here may be the biggest breakthrough on the means to measure potential successful technological inventions.

Let’s choose a current topical example, such as cryptocurrency, and ask the question.

Is cryptocurrency an effective functional currency?

Using the 3X3X3 Process.

It’s a Type 3 invention, its design and organisation are new. So, it’s easily classified as an invention.

The function of money according to some is threefold – it’s a means of exchange, store of value and means of account.

Is the functionality, how well it enables those functions, of crypto in terms of cost, precision and speed (timing) more functional than normal currency?

At a glance, crypto does not function well in any of the three measures of functionality. It’s not cheaper, it’s not more precise in the task of carrying out those three functions, and finally, it’s not faster in carrying out the three functions of money.

The very quick answer, without going into any depth on the subject, to the question is ‘crypto is not an effective currency’ by these measures. It may well not even be a currency; it may be something else.

Gavin Ritz is a successful entrepreneur, inventor, educator and businessman who has commercialised many products internationally in several consumer and high-tech markets (architectural hardware, exotic semiconductors, breakthrough neonatal masks). His commercialisation experience includes products for human resources, building products, consumer products, medical devices and high-tech products.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.