The pages of our national newspapers are littered with debate about the merits of the Albanese government’s Future Made in Australia policy. Yet, the one factor that supporters and opponents equally ignore is that no matter your vision for the future, economic power in the 21st century correlates with scientific power.

Only nations with strong, innovative science sectors that seek out new knowledge and understanding, work with industry, and are supported by government can prosper in the hypercompetitive world we live in. The question is — does Australia possess the sovereign scientific capability to support our ambitions?

Does our science and innovation system have the capacity and capability to underpin the energy transition we must make, to enable Australians to develop and adopt rapidly emerging new technologies, to support the health and medical needs of a growing and ageing population? And can it deliver the health and lifestyle advances we have come to expect?

The short answer is, we don’t know.

The Australian Academy of Science is developing a ten-year plan – Australian Science, Australia’s Future: Science 2035 – that will identify critical gaps in our science capability, structures and policies, that if left unaddressed, will limit our national and global ambitions.

The plan will equip governments and industry with the evidence they need to address capability gaps, direct resources strategically, and take a whole-of-system approach so Australia can confidently put its best foot forward.

To date, Australia has prioritised short-term needs over preparing for our nation’s changing needs. This means that our science and innovation system more closely resembles a patchwork of band-aids, rather than a finely calibrated system that is interconnected, responsive and resilient to change.

This approach has delivered us research and development (R&D) investment across 14 portfolios and approximately 200 programs that operate largely in isolation. And a big slice of the R&D pie –the R&D Tax Incentive – is poorly targeted. Imagine running a business that doesn’t critically examine the effectiveness of an incentive that absorbs 25 per cent ($3.2 billion and growing) of your operating budget.

Any rigorous capability analysis must take a system-wide approach to examine policies, resources and structures across schools, universities, VET, science-based institutions, industry and government. That’s why we are convening stakeholders from a range of disciplines and sectors to evaluate system capability.

If Australia gets this right, a strong science system that engages effectively with industry and government can diversify our economy making it more resistant to shock, add to productivity, provide sovereign capability that generates jobs, and improve our overall well-being.

If you were rapidly falling behind the rest of the world in terms of R&D investment, as Australia is, you would at least want to be investing in activities that deliver best bang for buck.

So, how we spend our $12 billion in annual R&D investment matters, but how and where we grow that investment, so we remain globally competitive, able to meet challenges and grasp new opportunities matters even more.

Australian Science, Australia’s Future: Science 2035 will help governments and others take a more targeted and informed approach.

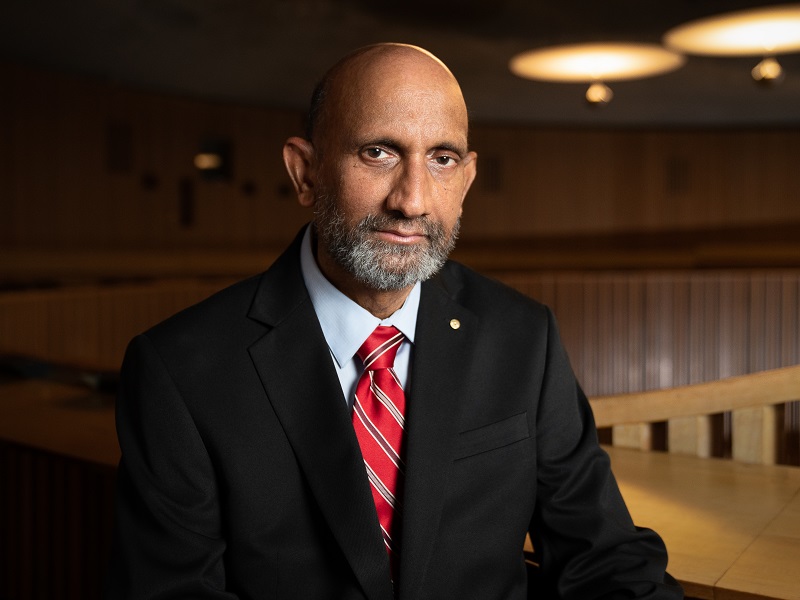

Professor Chennupati Jagadish is the president of the Australian Academy of Science and the head of the Semiconductor Optoelectronics and Nanotechnology Group at the Australian National University.

Do you know more? Contact James Riley via Email.